Commercial Fishing

Commercial fishing

Commercial fishing, when managed properly, can provide consumers with a local, healthy, and sustainable Great Lakes food source — and can help support a lake-based economy. Commercial fisheries provide fresh or preserved fish and fish products for grocery stores, farmers markets, and local shops around the Great Lakes.

In the 19th century, many important Great Lakes fish stocks collapsed due to overfishing, invasive species, and environmental degradation. Fisheries managers have since recognized the importance of closely monitoring harvest rates so they can make sure fish populations stay at healthy levels. Today, commercial harvest rights are divided among Canadian, U.S., and tribal fishing operations. Managers place great emphasis on shared and multiple uses of the Great Lakes fishery, balancing the harvests from both the sport and commercial fisheries.

Most commercial fishing in the region is done with gill nets or trap nets, although trawls are used in certain places. Gill nets are size-selective square mesh panels that allow smaller fish to swim through without getting caught. Trap nets funnel fish into a net box where they can swim freely before being retrieved. Learn more about commercial fishing gear on our commercial fishing net safety page.

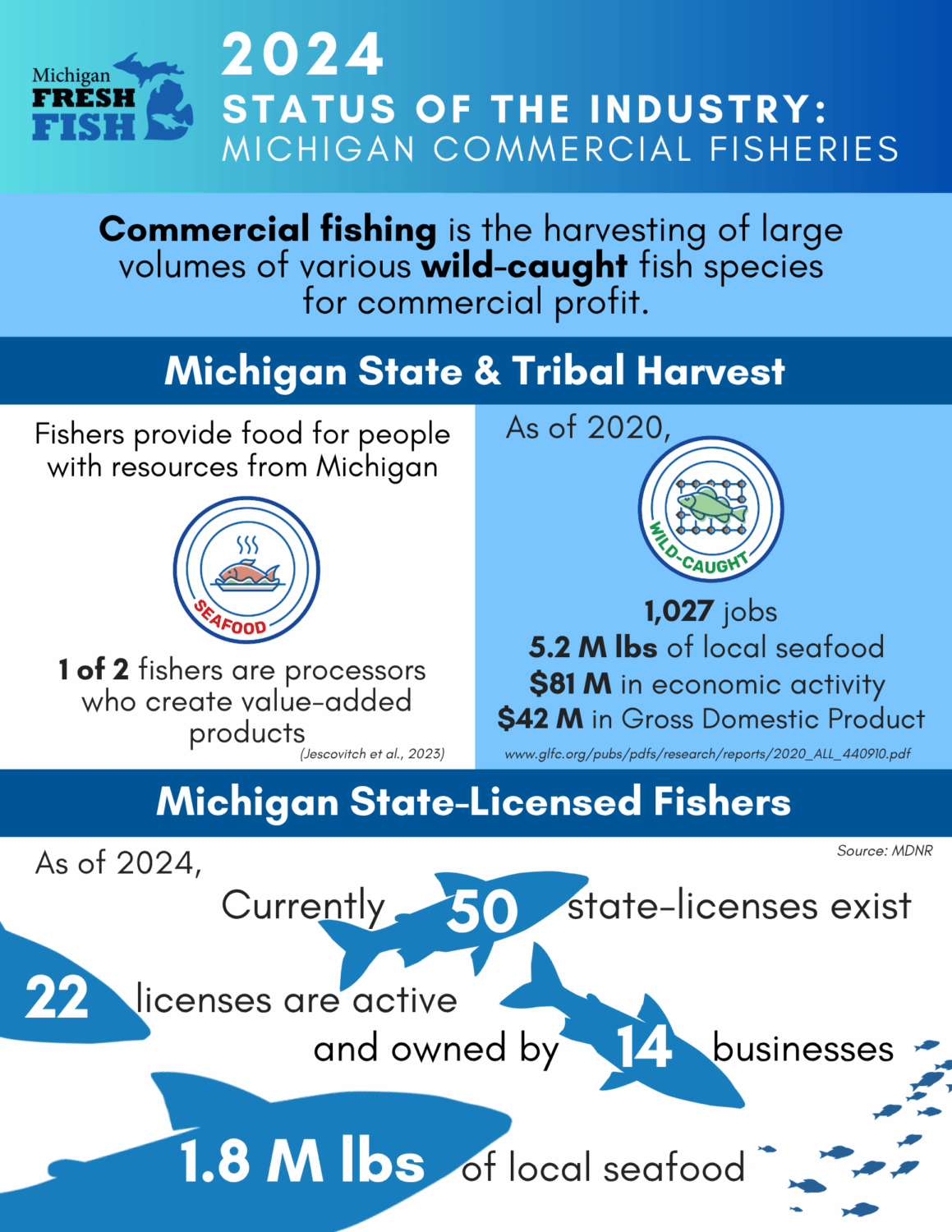

Value of commercial fishing

In 2015, the commercial fishermen in the U.S. waters of the Great Lakes brought in nearly 14.7 million pounds of fish with a landed (dockside or wholesale) value of $19.2 million. The same year, Canadian commercial operators harvested nearly 26.5 million pounds with a landed value of about $27.4 million. The processed (retail) value of these commercial harvests is significantly higher than the landed, wholesale value. For example, in Canada, the processed value of the commercial harvest is estimated to be at least five times more than the landed value, as processed fish are filleted, deboned, and packaged for sale.

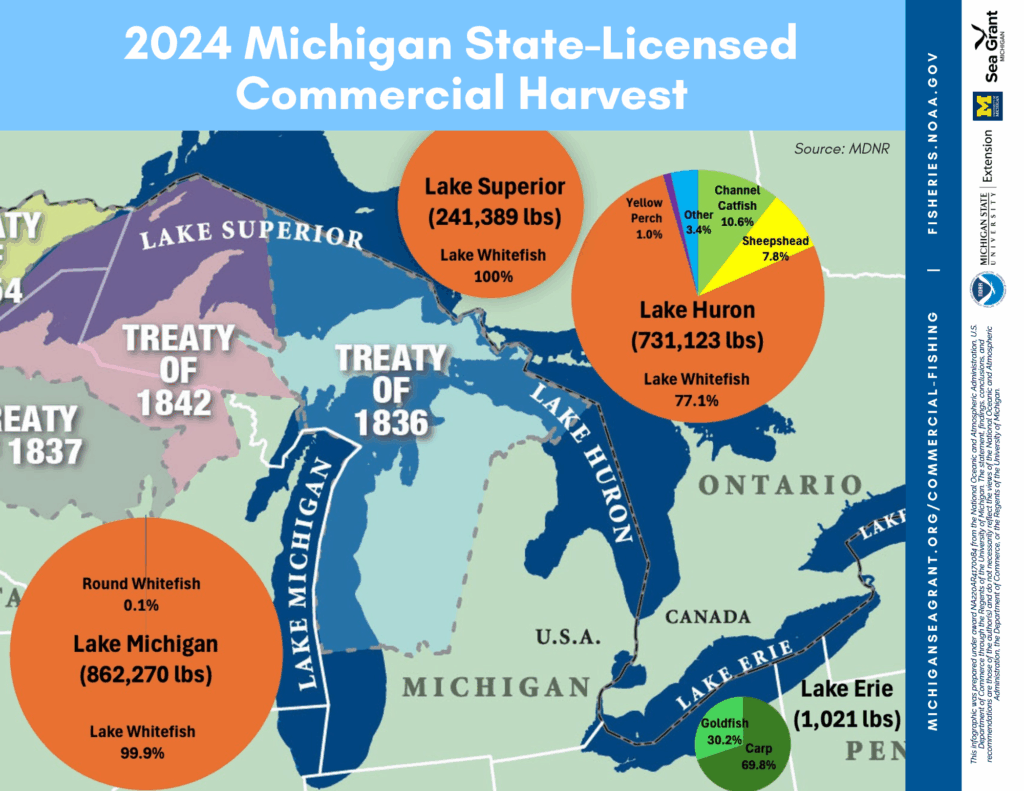

The most profitable species landed in U.S. and Canadian waters in 2015 were yellow perch, lake whitefish, and walleye. Lake whitefish is the most harvested fish in Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron. Despite its small size, Lake Erie boasts the greatest commercial harvest of the region, with efforts mostly focused on yellow perch, walleye, and rainbow smelt. Lake whitefish and yellow perch are commonly caught in Lake Ontario’s small commercial fishery. Other primary catches in the region include white bass, white perch, cisco (lake herring), lake trout, catfish, freshwater drum, and bloater (chubs).

Tribal fishing rights

Fishing and the use of gill nets for food and trade were important to the Great Lakes Tribes before and after European settlement. Great Lakes Tribes developed a life patterned around lakeside fishing villages with small gardens to supplement their diets.

Today, both the U.S and Canadian governments have treaties with sovereign tribal nations that outline access to Great Lakes fisheries resources. In U.S. waters, western Lake Superior is regulated under the Treaty of 1842, while the Treaty of 1836 involves eastern Lake Superior and northern Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. The Treaty of 1836 has been updated and reaffirmed several times, culminating in a 20-year Consent Degree signed by the U.S. government and five Great Lakes Tribes in 2000. The agreement expires in 2020, opening the door for new discussions and agreements about fish harvest and allocation among the state and tribes.

Subsistence fishing

The Great Lakes also support a subsistence fishery. Subsistence fishing is classified as fishing for personal or family consumption or use, including for ceremonial purposes.

Many people throughout the region — who fish with or without sport licenses — also rely on fish as a primary food source. For example, there is a population of fishers in urban areas such as Milwaukee, Chicago, and Detroit for whom fish is a primary food source. Furthermore, anglers throughout the region, particularly the northern reaches of the Great Lakes, report that they rely on fishing as a means of procuring food for themselves and their families. Subsistence fishers may use hook and line, nets, or spears to harvest fish.