By Brenna Friday, 2024-25 Knauss Fellow

For many, a visit to a Smithsonian Museum is a highlight of any trip to Washington, DC. As someone who recently moved to our nation’s capital, the novelty of stepping into any of these museums still stands.

My name is Brenna Friday, and I’m currently a Knauss Sea Grant Marine Policy Fellow working in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). I moved from Detroit to Washington in February 2024 to step into a role of Nutrient, Harmful Algal Bloom (HABs), and Biocriteria Fellow in the EPA’s Office of Water’s Office of Science and Technology. Since then, I’ve contributed to a diversity of projects, from organizing webinars on nutrient pollution to drafting reports for Congress on HABs that have each taught me something new about the complex relationship between environmental science and water quality policy.

Before I started my fellowship, I attended Wayne State University as a doctoral student studying how developing frogs, toads, and salamanders may be impacted by harmful algal blooms in their environments. I decided to explore this main question in graduate school after a lifetime love of amphibians and some prior formative research experiences. From elementary zoo field trips to college classrooms, I kept hearing about amphibians’ roles as metaphorical “canaries in the coalmines” whose sensitivity to contaminants could alert humans to environmental issues. Their biphasic life cycles and permeable skins contribute to likely exposure to pesticides, toxins, and other chemicals in both their freshwater and terrestrial environments. These animals may be slimy and sometimes bumpy (not warty!), but people of all ages seem to connect with their big eyes and goofy smile.

Examples from the Smithsonian’s off exhibit amphibian collection. Photo: Brenna Friday

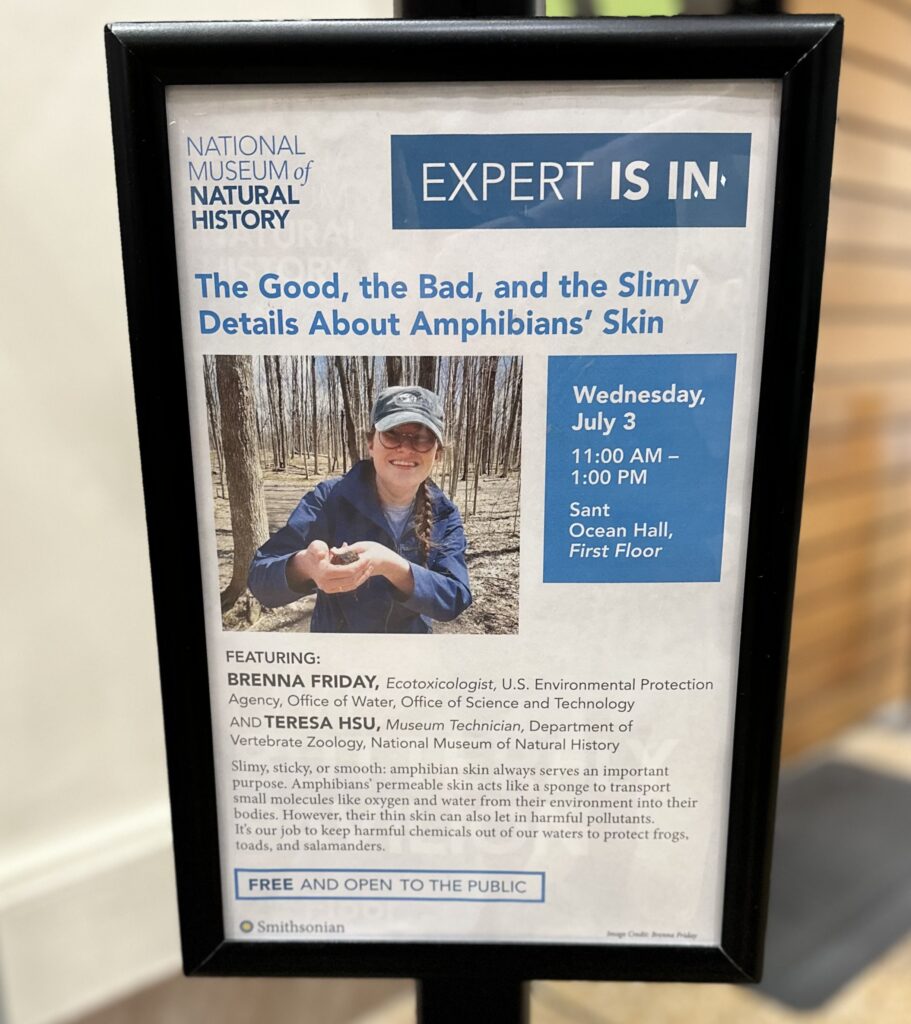

When an opportunity was presented to me to chat with visitors about amphibians on the floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), you could say I leapt for it. An ongoing collaboration between the NMNH team and the Knauss Fellowship program allows for fellows to design their own “Expert Is In” program to educate museum visitors on a topic related to their scientific expertise.

A flyer advertising the Expert Is In event. Photo: Brenna Friday

The incredible team from the NMNH Office of Education, Outreach, and Visitor Experience allows fellows to design their own educational program with consistent check-ins and guidance on effective science communication strategies. Our first requirement was to attend an informational training on visitor interaction that was open to us fellows along with other interested museum staff. During brief introductions of everyone in our group, I was immediately excited to meet Teresa Hsu, a museum technician in the Department of Vertebrate Zoology focused on herpetofauna. Amphibians are sometimes categorized with reptiles under the term “herpetofauna” in which these evolutionarily distinct animals are brought together based on shared cold-blooded and four-limbed traits. Teresa was also attending the training to host her own Expert Is In session in the future, and we immediately connected on our shared interest in amphibians.

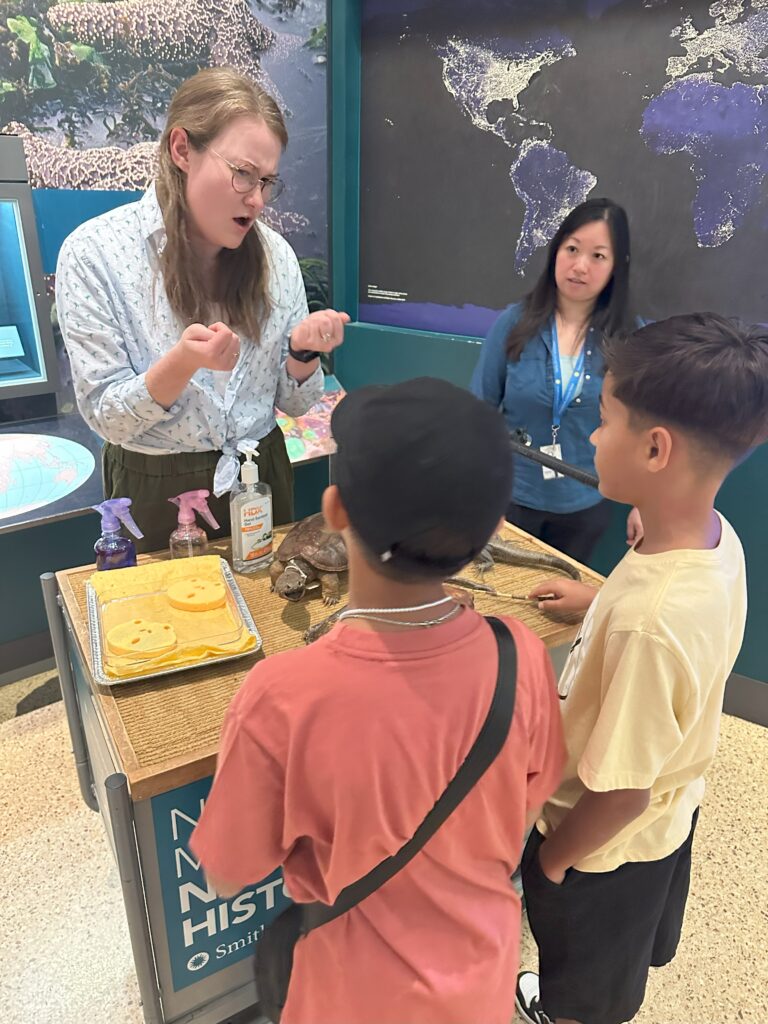

Teresa and Brenna prepare to engage visitors on the differences between amphibians’ and reptiles’ thick, armored scales and shells. Photo: Brenna Friday

We kept talking after this first training and decided to codesign an Expert Is In program on the sensitivity of amphibians to chemicals in their environment. To share this message, we designed two hands-on activities that compared amphibians’ smooth, thin skin with reptiles’ strong, armored scales and shells. Teresa’s deep knowledge of the museum’s vertebrate collections helped us narrow in on some specimens that would be wonderful representatives of different vertebrate groups. Teresa generously offered to show me some of the off-exhibit collections so that I could weigh in on which specific animals would be best to include in our program. This look “behind the scenes” was eye-opening to the incredible size of the Smithsonian collection, as well as the intricate research questions that could be investigated thanks to the preservation and safe-keeping of millions of organisms. I was excited to see some rare, now extinct organisms safely kept in rows of library-like shelves alongside more common organisms or even human-made replicas. For activities like ours where we would encourage visitors to touch and compare specimens, it made sense to use a mix of animal models and commonly preserved specimens. After hours of consulting the collection and discussing our goals for the event, we settled on 5 exemplary specimens for our Expert Is In activity.

Examples from the Smithsonian’s off exhibit amphibian collection. Photos: Brenna Friday

On the day of our event, Teresa and I set up our cart in the NMNH Ocean Hall and went over our key messages for visitors one last time. We wanted to educate visitors on amphibians’ sensitive skin and inspire them to take steps to limit handling and/or transferring chemical exposures to amphibians found in their backyards. To share our message, we encouraged visitors to touch preserved reptile and amphibian specimens and share how each animal’s exterior felt on their fingers. We also used frog-shaped sponges and water with food coloring to demonstrate how clean and “contaminated” waters can both be absorbed through amphibian skin. From these two visual and tactile activities, many visitors responded with questions or personal stories about interacting with amphibians in their own lives. Sometimes these discussions explored how or why amphibians lived with such permeable barriers to chemicals, but other times folks were more interested in learning about how the specimens were preserved or how they arrived in the museum collection. Together, Teresa and I spoke to about 360 visitors of all ages during our Expert Is In session. We welcomed any and all questions, but I believe that most visitors walked away with a new understanding of how the sunscreen on our hands and pesticides on our crops may not harm us humans but may negatively impact our more sensitive amphibian neighbors.

Teresa and Brenna speak to museum visitors about amphibian conservation. Photo: Brenna Friday

This experience has undoubtedly been one of the highlights of my Knauss Fellowship year so far. It allowed me to develop my science communication skills and deepen my understanding of how museum collections may be used in research and conservation. I am so fortunate to have connected with people like Teresa who have gone out of their way to teach me about the day-to-day responsibilities and the overarching mission behind their work. From the floor of the Smithsonian to my desk at the Environmental Protection Agency, I have seen countless examples of how necessary it is for us scientists to effectively communicate complex ideas to diverse audiences. Whether I’m speaking to children at a museum or policy directors, I know that experiences like this are what prepare me for discussions that may make a difference in the future of our country’s freshwater environments, especially for those slimy, significant, amphibian inhabitants.