The Laurentian Great Lakes provide drinking water for millions of people, habitat for thousands of species, and unparalleled economic, cultural, and recreational value to an entire region. Unfortunately, Michigan’s coastal and open waters face challenges from legacy contamination, climate change, and loss of biodiversity, threats that are also occurring to lands and waters across the world. In an effort to address these issues, the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP 15) Convention on Biodiversity in 2022 established a global goal to conserve 30% of land and water by 2030, also known as 30×30. More than 100 countries, including the United States, agreed to pursue the 30×30 goal.

The Great Lakes – representing 20% of the world’s freshwater supply and 40% of Michigan’s area – are crucial to achieving this goal. In response, a Michigan Sea Grant (MISG)-funded research project, led by Jennifer Read, director of the University of Michigan Water Center, explored how Michigan could conserve 30% of Michigan’s land and water by 2030 through community and state collaboration.

The primary objectives of this project were to develop actionable recommendations to guide Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources and The Nature Conservancy in integrating

Great Lakes conservation into statewide planning. The project team conducted an extensive literature and document review, interviewed 48 individuals, and held three focus groups with agency staff, researchers, local leaders, Tribal staff, and other key stakeholders and rights holders. Additionally, the team developed GIS maps to visualize key data and identify opportunities for enhanced conservation. They also used case studies from three distinct coastal communities – Sault Ste. Marie, Alpena, and Muskegon – that highlight the complexity of Michigan’s Great Lakes regions.

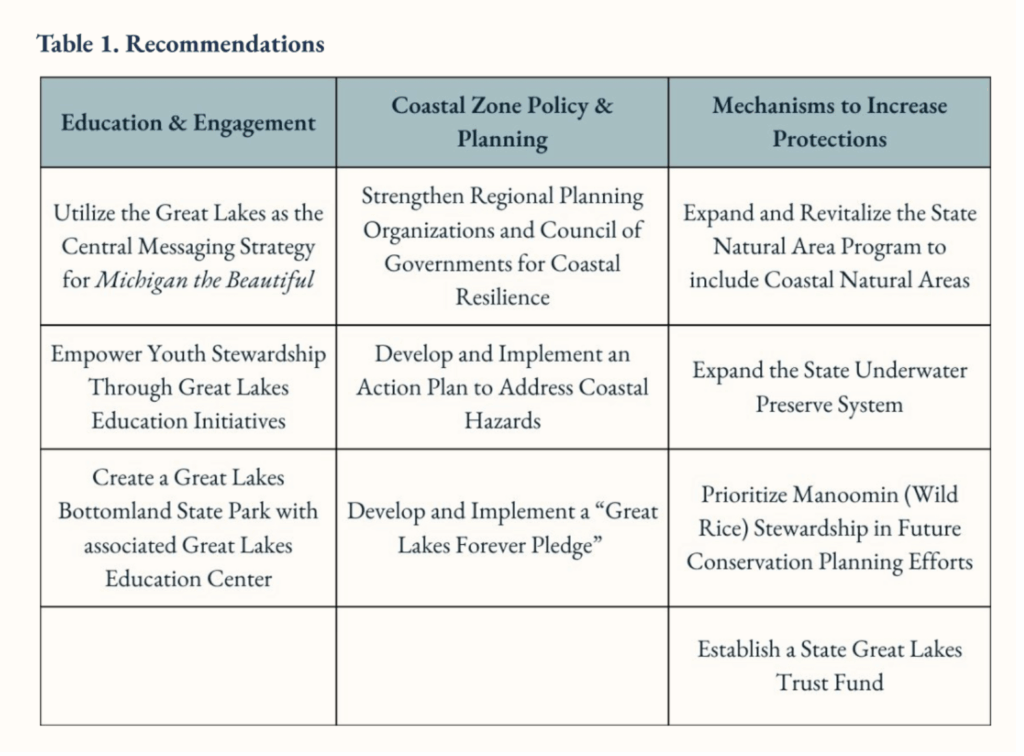

This research led to a set of ten recommendations designed to enhance Michigan’s conservation efforts (see Table 1). The details of their findings are captured in a final report.

Importance of Collaboration

Working alongside the Michigan DNR, The Nature Conservancy, University of Michigan Water Center, and Michigan Sea Grant, the research team assessed the current state of protections contributing to Michigan’s goal of conserving 30% of its lands and waters by 2030. They found that 19.2% of Michigan’s land is currently under protection, and 24.23% of jurisdictional waters are currently designated under some level of state or federal protection. These designations vary widely in management capacity and conservation impact, however; most provide designations without active management strategies, and provide protection for cultural resources rather than ecological resources.

The team identified four key focal areas for increasing conservation in the Great Lakes: enhancing biodiversity, improving coastal management, strengthening education and engagement, and increasing funding. It recommended that the Department of Natural Resources should play a central role in implementation along with collaboration across federal, Tribal, state, and local governments, as well as non-governmental organizations.

Developing a Solid Plan

One highlight of the findings is that Michigan has a strong foundation to build on, with existing programs that emphasize collaboration, habitat restoration, and community stewardship. Initiatives through the Michigan Coastal Management Program, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), Michigan Sea Grant, local planning groups, MSU extension, and other partnerships, for example, show the effectiveness of place-based collaboration and community engagement.

The report suggested scaling up place-based, community-driven approaches is critical to protecting biodiversity and ensuring long-term resilience. Learning from other states’ 30×30 strategies can help refine Michigan’s policies and innovation in freshwater protection. Additionally, lessons from other leading states, such as California’s marine protected area network and Illinois’ Prairie State Conservation Plan, offer valuable models for creating durable governance structures, long-term funding strategies, and inclusive public engagement processes.

The report found that any program focused on the future of the Great Lakes must be informed by the experiences of Michigan’s coastal residents and communities. While Michigan’s coastal communities share common historical ties to Great Lakes industries such as shipping, fishing, and tourism, each community has its own unique social dynamics and conservation opportunities. Each of the three case study communities has a key anchor institution, such as Lake Superior State University’s Center for Freshwater Research and Education in Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Alpena, and Grand Valley State University’s Annis Water Resource Institute in Muskegon. All of these anchor institutions have deeply impacted their communities and have played a significant role in the restoration and revitalization process.

With 3,288 miles of Great Lakes shoreline and 38,000 square miles of open Great Lakes waters and bottomlands, the State of Michigan can play a major role in determining the health and vitality of 20% of the world’s freshwater.

More information and additional resources can be found here.