Editor’s note: All images in this article are courtesy of Billy Keiper from the recorded webinar linked below.

A Michigan Sea Grant program, a keen-eyed pond patroller, and a swift state push have gotten an aggressive invasive plant back under control in southwest Michigan.

Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) Aquatic Biologist Billy Keiper spoke during a June 25 webinar called “Digging In: Michigan’s Unconventional Response to Hydrilla” as part of EGLE’s “NotMISpecies” webinar series. He highlighted the cooperation and good timing that helped the state halt a growing infestation of the notoriously pervasive hydrilla.

Let’s get back to the beginning

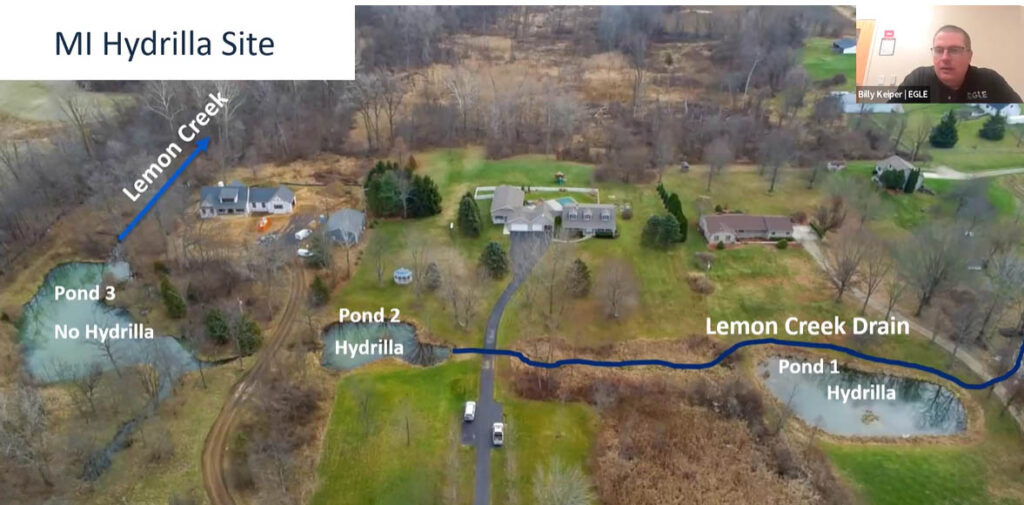

In September 2023, EGLE publicly confirmed that small pockets of hydrilla had been found in two residential ponds in Berrien Springs in southwest Michigan.

This sparked a flurry of activity — hydrilla is known as one of the most aggressively invasive plants in the world. It spreads quickly and can tolerate low light and poor water quality, giving it an advantage over native aquatic species. Read hydrilla’s species profile on the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS).

Alex Florian coordinates the Southwest by Southwest Corner Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (SWxSW Corner CISMA). He found the hydrilla while monitoring ponds previously flagged for parrot feather, another invasive plant prohibited in Michigan. Alex credited Michigan Sea Grant’s MI Paddle Stewards program for helping him recognize and correctly identify hydrilla.

Michigan meets the moment

Thanks to Alex’s report, EGLE’s Michigan Invasive Species Program launched a rapid response plan to treat existing hydrilla plants in the ponds and prevent them from spreading into additional waterways. “Hydrilla is the highest risk species, there’s no doubt about that,” stated project lead Billy Keiper during the EGLE webinar.

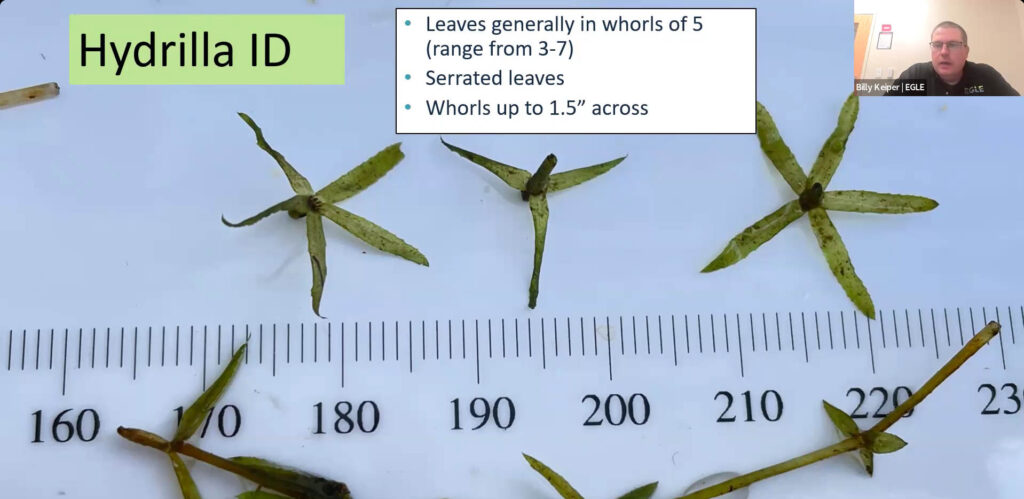

Hydrilla grows whorls of serrated leaves on slender stems that can reach as long as 30 feet. The Asian native was initially detected in Florida in the 1950s and has now spread as far as Ohio and New York. Because of its potential for squeezing out native aquatic plants and clogging waterways, hydrilla is prohibited in the United States and Canada and is included on Michigan’s invasive species watchlist.

Despite the bans, traces of hydrilla can still show up alongside popular aquarium and water garden plants, opening possible routes for bits of stems, leaves, or tiny eraser-sized tubers to hitchhike into ornamental lakes and ponds. Hydrilla easily breaks into fragments that can be transported across waterways on boats, trailers, fishing gear, and other equipment. Any portion of the plant can potentially take root and start a new population. Hydrilla tubers can last up to a decade in underwater sediment, making eradication a long, intensive, and expensive prospect.

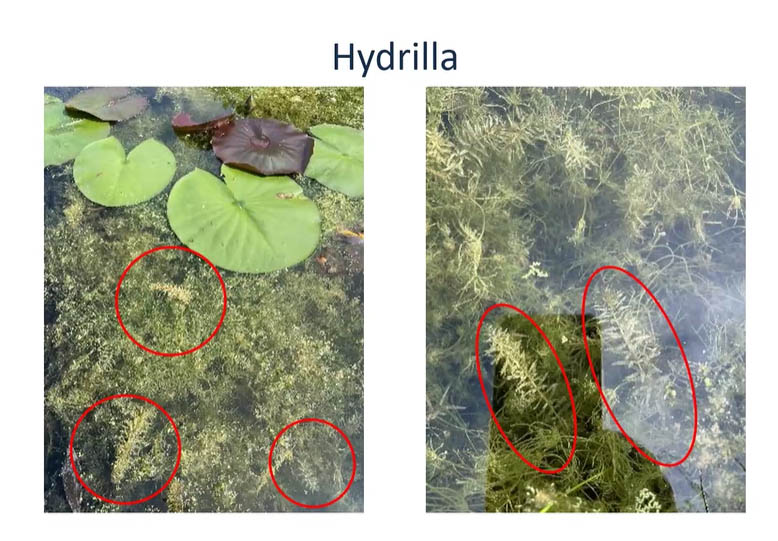

Hydrilla can also be challenging for even professionals to spot and identify. The whole plant can remain underwater, barely visible from the surface aside from an occasional tiny white flower. The plant also closely resembles a common Michigan native, Elodea. However, hydrilla’s serrated leaves typically spiral around its stem in whorls of five rather than Elodea’s three.

Thankfully, due to his recent MI Paddle Stewards training, CISMA Coordinator Alex Florian was primed to look closely at any aquatic plant. On September 13, 2023, he was checking three residential ponds that had been treated for invasive parrot feather since 2020. He spotted what looked like hydrilla among the other submerged greenery and knew he needed to act fast. Within 11 days, his reported identification had been confirmed, the ponds were carefully surveyed, and EGLE began herbicide treatments.

EGLE found small pockets of hydrilla plants and tubers in two of the three residential ponds, with no sign of further spread. Based on property records, EGLE concluded that the hydrilla had likely been present for several years, possibly introduced as a few tubers or stem fragments tucked into pots of non-native pink water lilies.

According to Billy Keiper, this was the best possible scenario under the circumstances. If left unchecked, the small pockets they discovered could easily have found favorable habitat in the nearby St. Joseph River and worked their way toward Lake Michigan.

Dredge and drain

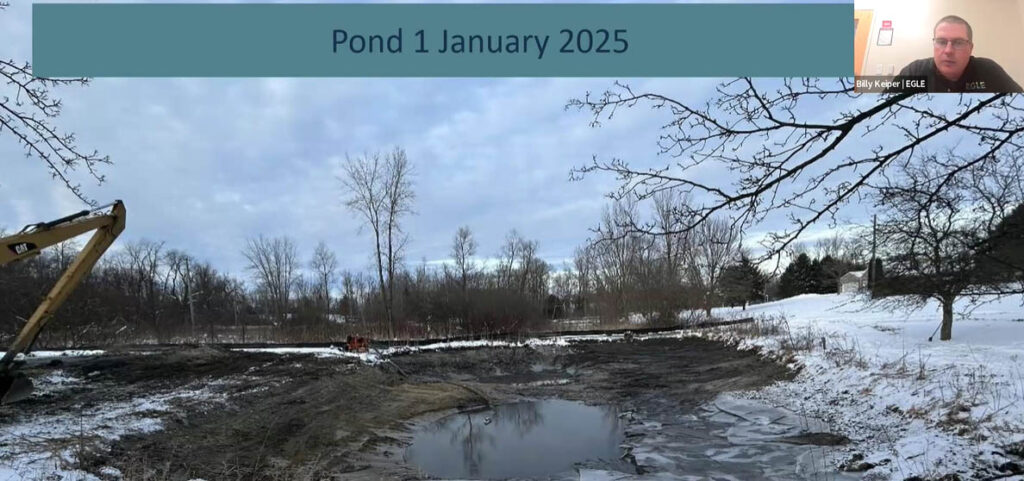

Confident that the infestation was small and localized, but given the daunting risk of spread, EGLE decided the situation merited a strong response. In 2024, they used herbicides to effectively wipe out all plant growth in the ponds. This limited hydrilla’s ability to regrow and produce tubers while EGLE worked to clear the sediments of fragments that could kick off a fresh infestation.

State agency staff worked closely with the three adjacent property owners to weigh solutions for the ponds and nearby wetlands. They could choose to do nothing, to apply herbicide every year for 6-8 years, to fill in the ponds and dig new ones, or to mechanically remove all traces of the invasive plant in the existing ponds — hopefully for good.

With the homeowners’ permission, EGLE moved ahead with the mechanical solution: draining and dredging the ponds. The strategy wouldn’t be cheap, but it offered a shorter timeline and a permanent solution, and the state could make every effort to leave the pond system better than they’d found it.

State agency staff started by pumping water into mesh bags that could slowly drain into the nearby wetland while filtering out any plant fragments. As they worked, they watched carefully for frogs and fish that could be stashed in buckets and temporarily transferred to safer waters.

After dredging and burying the bottom sediments, EGLE staff let the ponds naturally, and the shorelines were relandscaped. Then it was time to watch and wait.

Billy Keiper reported that by June 2025, the ponds have already started to rebound. The scraped sediments are now blanketed with a beneficial native algae called Chara. The fish and frogs were restored to their homes, and a fresh crop of tadpoles and fish larvae signal strong populations to come. The wetlands are intact, and the surrounding property is recovering well. EGLE staff anticipate transplanting native aquatic plants into the ponds in 2026 to boost their road to recovery.

Monitoring staff have been donning snorkels to comb through the greenery for any telltale five-whorled leaves. Nothing has turned up as of June 2025. Monthly monitoring will continue for three years, and SWxSW Corner CISMA received funding for 2024 and 2025 to support intensive sampling in the broader area to rule out any chance of spread.

Training early detectors

Although this operation looks like a success, it’s only a matter of time before hydrilla is found in Michigan again. Populations were detected in Leamington, Ontario, in mid-2024, and in Chicago that fall. If it becomes established in Michigan, hydrilla will be essentially impossible to eradicate.

Early detection can pay off — literally. Billy reported that the hydrilla project cost $239,000, split between the EGLE general fund and a Michigan invasive species immediate response fund. That price tag pales in comparison to the recent cost of eradicating a more established population in an Indiana lake: $2 million and the shuttering of the public lake for 10 years.

In the interest of empowering early detectors, EGLE, Michigan State University Extension, CISMAs, Michigan Sea Grant, and many other organizations are working hard to train as many people as possible to spot and report hydrilla and other watchlist species.

As Billy reiterated, it’s always worth reporting a plant or organism that doesn’t look quite right. Take a few clear photos of the plant in its habitat, then out of the water against a plain background (such as a large rock or piece of paper). Send the photos and location information to the EGLE Aquatic Invasive Species Program at [email protected] or use the reporting tool from the Midwest Invasive Species Information Network (MISIN).

Here are a few other opportunities for Michiganders interested in keeping their favorite water bodies safe and healthy:

- Join Michigan Clean Water Corps (MiCorps), a network of volunteer water quality monitoring programs.

- Add your local lake to the Exotic Aquatic Plant Watch.

- Explore online and in-person MI Paddle Stewards programs to brush up on ID and reporting skills.

- Download the MISIN mobile app for easy reporting on the go.

- Register for Michigan State University Conservation Stewards, now open in many counties for Fall 2025.